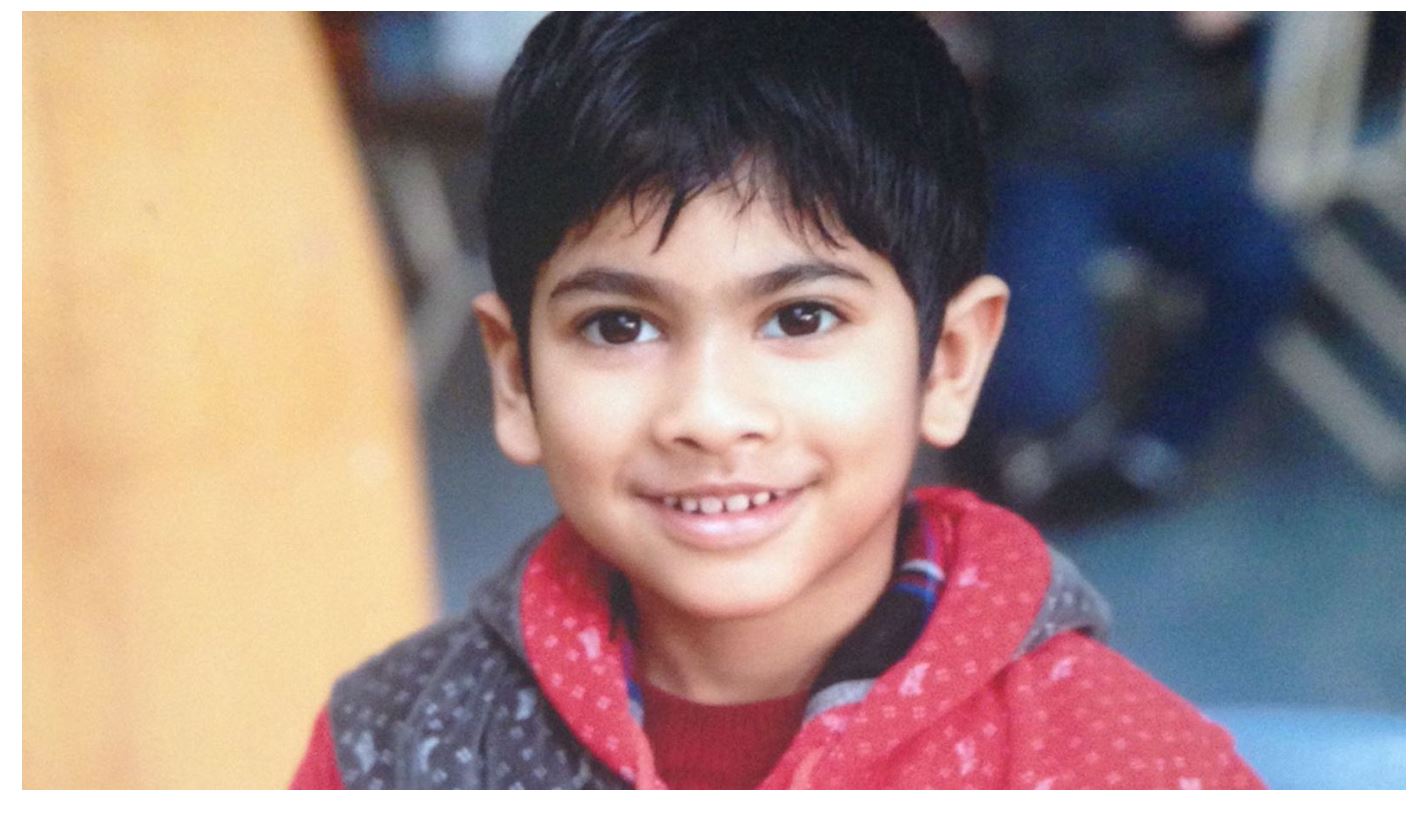

The Bangladeshi parents of a six-year-old boy born in Australia are calling on the government to intervene after spending more than four years under the threat of deportation. Adyan bin Hasan is a happy and energetic child who loves to run, play and ride his scooter around his home in Geelong, Victoria. But Adyan has been deemed a burden on the taxpayer because he has mild cerebral palsy and a mild intellectual disability. The conditions, caused by a stroke at birth, were so slight most people did not realise Adyan had them, his father Mahedi Bhuiyan said. However, when Dr Bhuiyan and Adyan’s mother Rebaka Sultana filed for permanent residency in March 2016, their application was denied under Australia’s strict “one fails all fail” visa health criteria. Dr Bhuiyan, who is a structural engineer, had been nominated to apply for a permanent skilled migration visa after finishing his PhD at Deakin University. Ms Sultana was a medical doctor in Bangladesh and is currently preparing to sit examinations to be registered to practice in Australia. Dr Bhuiyan said he had expected their visa application to be a straightforward process and was left in shock when it was rejected. “I could not sleep for the first week. Even now, I can’t sleep more than one or two hours a night because I feel that I’m dreaming actually. I am thinking everything will go away once I wake up,” he said. What followed was a lengthy process of appealing the decision through the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), which ultimately upheld the Immigration Department’s decision in late 2018. Not willing to give up on the family’s dream of living in Australia, Dr Bhuiyan applied for a ministerial intervention last August and the case now rests with Assistant Minister for Customs, Community Safety and Multicultural Affairs Jason Wood, who has the discretionary power to grant a visa. In February this year, the family underwent further police checks and medical assessments at the request of the NSW Ministerial Intervention Office, as well as obtaining letters from Adyan’s paediatrician and school. Dr Bhuiyan said his son was doing well at his mainstream primary school and only needed a small amount of extra support. “His condition is good, he can run and read and write. He rides his scooter to school,” he said. The letter from Adyan’s paediatrician, seen by nine.com.au, states his patient had made “superb progress over the years” and was now fully mobile; able to run, climb stairs and ride a scooter. Adyan was able to write and draw, had good language skills and would only require modest support going forward, the letter stated. For the past four years, the family have been living in Australia on a bridging visa, which needs to be extended every two-and-a-half months. Dr Bhuiyan said waiting for so long and not knowing what would happen to his family had taken an enormous toll. “We feel that we are unable to breathe. I don’t know how long I will survive. I am tired and my hands are tied,” he said. Dr Bhuiyan said he feared if they were deported his son would face discrimination in Bangladesh, where people with even mild disabilities can be shunned because of superstitions. Under the conditions of his bridging visa, only one of Adyan’s parents is able to work and neither are able to get full-time jobs. Dr Bhuiyan said he was currently working two casual jobs at Coles and 7-Eleven to support his family, but it was a sacrifice he was willing to make. “It is nothing that I am doing this, all the things I am doing is for the hope of my son,” he said. Dr Bhuiyan said he still believed the Australia government would show compassion towards his family. “I understand my son needs some help but he is not a burden. All I am asking is please give us a chance.” Other families facing deportation under circumstances similar to Adyan’s have been granted a ministerial intervention. Last year, the Irish parents of Australian-born toddler Darragh Hyde were granted permanent residency after he was initially deemed a taxpayer burden because of his cystic fibrosis. The Department of Home Affairs is yet to respond to nine.com.au’s request for comment. While the department does not usually comment on individual cases, it has previously said: “Most visas require applicants to meet the migration health requirement set out in Australian migration law. The health requirement is not condition-specific and the assessment is undertaken individually for each applicant based on their condition and level of severity.” “It is an objective assessment to determine whether the care of the individual during their stay in Australia would likely result in significant costs to the Australian community or prejudice the access of Australian citizens and permanent residents to services in short supply. “For certain visas, primary criteria for the grant of the visa requires that all members of a family unit satisfy certain requirements. If one of the members of a family unit does not satisfy these requirements, then the primary applicant will not meet the criteria for the grant of the visa.” https://www.9news.com.au/national/australia-immigration-familys-permanent-visa-denied-over-sons-mild-disability/6c3d3de2-b64e-4a6e-9738-d81f77bbe798